The Mighty F = ma

This equation is one of the most useful in classical physics. It is a concise statement of Isaac Newton's Second Law of Motion, holding both the proportions and vectors of the Second Law. It translates as:

The net force on an object is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by the acceleration of the object.

Or some simply say:

Force equals mass times acceleration.

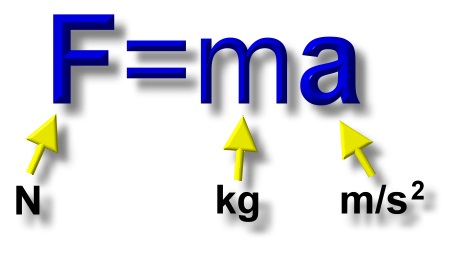

Units for force, mass, and acceleration

|

|

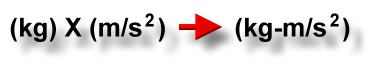

When you multiply a kilogram (mass unit) times a meter per second squared (acceleration unit) you get a kilogram-meter per second squared.

So a unit for force is actually the kilogram-meter per second squared. However, no one really says that. The unit for force is named after Isaac Newton, and it is called the 'Newton', abbreviated 'N'. One Newton is one kilogram-meter per second squared.

Another almost identical way to think about the force unit is that one Newton is the size of a force needed to accelerate a mass of one kilogram at a rate of one meter per second squared, as in:

Here is a slideshow that shows three basic problems using F=ma. Also presented is the algebra used to rearrange the formula when solving for mass or acceleration.

After going through the above slideshow, one might wonder how the units for these equations resolve. For example, the following is true:

a = F / m

But how does an acceleration unit (on the left) become the same as a force unit divided by a mass unit (on the right)? All of this is explained in the following scrolling panels.

Unit relationships for F=ma

Unit relationships for a=F/m

Unit relationships for m=F/a

Here are some problems that work with basic F=ma algebra. All of that is explained in the 'Calculating with F=ma' demonstration above. Each problem page has a back button that will return you to this page.

Here we will show that in the equation F=ma the acceleration vector, a, has the same direction as the net force vector, F.

First, recall that when we multiply a scalar times a vector, the result is a vector that has the same direction as the original. So if we multiply scalar 2 times vector P we get a vector as the result which has the same direction as vector P. We could give this result vector a name, say Q. This is all shown in the following animation:

Now let's see how all this works out with the F and the a vector in the equation F=ma. Note that the right side of the equation is mass times acceleration. Mass is a scalar, and acceleration is a vector. So the right side of this equation is a scalar times a vector. This multiplication yields a vector that is called the force vector, or F, which is on the left side of the equation.

As above with P and Q, vector a is in the same direction as vector F. Therefore, the acceleration of an object is in the same direction of the applied net force. Here is another animation showing all of this for the a and F vectors:

And so we have shown that the formula F=ma contains the information that an object's acceleration vector is aimed in the same direction as its applied net force vector.

Direct and inverse proportions

There is a direct proportion between acceleration and applied net force.

Information about direct proportions can be found here.

Let's see if the equation F=ma contains the direct proportion between force, F, and acceleration, a. That is, does F=ma contain the information that acceleration is directly proportional to the applied net force?

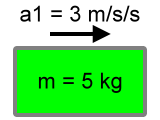

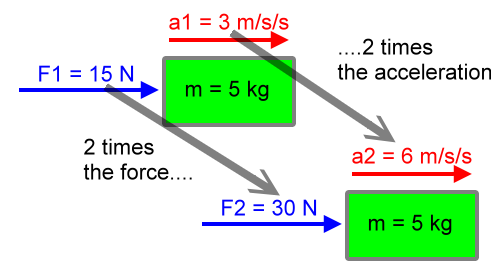

If acceleration is directly proportional to the applied net force, then by whatever factor acceleration changes, force changes by the same factor. To see this we will need to consider an object with constant mass. Let's consider an object with a mass of 5 kg.

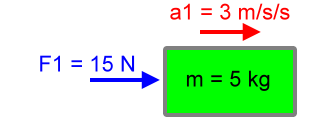

Suppose this object has an acceleration of 3 m/s2. Let's call this a1. So:

|

a1 = 3 m/s2 |

|

What force is necessary to cause this acceleration to our 5 kg object? Let's figure that out and call it F1:

|

F1 = ma1 F1 = (5 kg)(3 m/s2) F1 = 15 N |

|

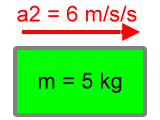

Now let's think about this object when it is moving at twice this acceleration. That is, we will change the acceleration by a factor of 2. Let's call this new acceleration a2. So:

|

a2 = 2(a1) = 2(3 m/s2) = 6 m/s2 |

|

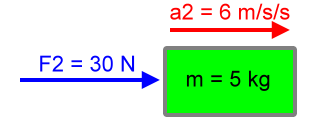

What force is now necessary to cause this new acceleration, a2? We will call this force F2, and here is its calculation:

|

F2 = ma2 F2 = (5 kg)(6 m/s2) F2 = 30 N |

|

Now that second force, 30 N, is twice the first force, 15 N:

F2 = 2F1

30 N = 2(15 N)

30 N = 30 N

And that second acceleration, 6 m/s2, is twice the first acceleration, 3 m/s2:

a2 = 2(a1)

6 m/s2 = 2(3 m/s2)

6 m/s2 = 6 m/s2

Clearly, both the acceleration and the force on this object change by the same factor, 2. These matching factor changes would occur for any factor change and for any constant mass. So the equation F=ma contains the direct proportion between acceleration and the applied net force.

The inverse proportion between acceleration and mass

Now, what about the inverse proportion between acceleration and mass, is that contained within F=ma?

Information about inverse proportions can be found here.

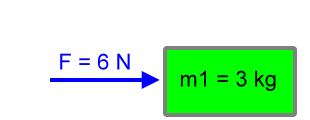

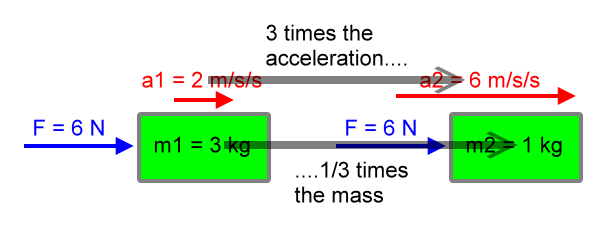

Let's consider two situations, each with the same applied net force, say 6 N. That is, object 1 will have a net force of 6 N applied to it, and so will object 2.

We will say our first object has a mass of 3 kg. So:

| m1 = 3 kg |

|

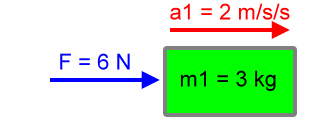

What will be the acceleration of this object? Let's call that acceleration a1, and let's solve for it using F=ma. So:

F = m1a1

Rearranging and calculating the above equation for acceleration we get:

|

a1 = F / m1 a1 = 6 N / 3 kg a1 = 2 m/s2 |

|

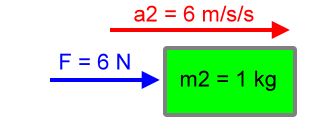

Now let's cut the mass to one-third. That is, we will consider a change in mass by a factor of 1/3. That would make the mass of object 2 to be 1 kg, or m2 = 1 kg. If we apply the same force, 6 N, to object 2, what will be its acceleration? Here's the calculation:

|

a2 = F / m2 a2 = 6 N / 1 kg a2 = 6 m/s2 |

|

So the second mass is 1/3 the first mass, since:

m2 = (1/3)m1

1 kg = (1/3)(3 kg)

1 kg = 1 kg

And the second acceleration is three times the first acceleration, as in:

a2 = (3)a1

6 m/s2 = (3)(2 m/s2)

6 m/s2 = 6 m/s2

Clearly, the acceleration and mass change by reciprocal (or inverse) factors. The factors are 3 and 1/3, respectively. Since these two quantities change by reciprocal (inverse) factors, these two quantities are in an inverse proportion.

There is really nothing special about our choice of factor changes here. Try changing the mass by a factor of 5 and calculate to see the acceleration change by a factor of 1/5.

Looks like the formula F=ma contains both the direct and inverse proportions we described in our main Newton's Second Law of Motion page.

Relationship to kinematics formulas

Let's see how F=ma works itself into the kinematics formulas for accelerated motion, effectively changing kinematics into dynamics.

Information about equations for accelerated motion can be found here.

These equations are presented here with the subscript 'i' meaning 'initial'. So this symbol:

vi

Would mean 'velocity initial' or 'the initial velocity'.

Now you are just as likely to see the subscript 'o' meaning 'original' used for exactly the same concept, the first, initial, or original. This symbol:

vo

Would mean 'velocity original' or 'the original velocity'.

So the subscripts 'i' and 'o' carry the same concept:

vi is the same as vo

Hopefully the above will clear up any problems over the way that these equations are presented on the Equations for Accelerated Motion page and the way they are presented here. Example problems follow.

As it turns out, since:

a = F / m

Knowing an object's mass and the net force on it is as good as knowing the acceleration of the object. Divide the net force by the mass, and you will find the acceleration of the object. Once the acceleration is known, you can use the kinematic equations to discover the motion which the object will undertake. With all of this you can figure out where things are going and when they will get there. Thank you, Isaac Newton.

Let's note the substitutions in the following kinematics equations.

d = vit + (1/2)at2

Displacement equals the initial (or original) velocity multiplied by time

plus one-half times the acceleration multiplied by time squared.

vf = vi + at

The final velocity is equal to the initial velocity plus the acceleration

multiplied by time.

vf2 = vi2

+ 2ad

The square of the final velocity is equal to the square of the initial

velocity plus two times the acceleration times the displacement.

Example dynamics problems

Following are some example problems showing how the above substitution allows us to understand the motion of an object and the forces causing its motion. The parameters for each example can be modified with the 'less' and 'greater' buttons. Adjust them to see how the calculations work in several situations.

So, to sum it up for F=ma:

- It's a concise and sufficient statement of Newton's Second Law of Motion.

- In vector form (F=ma, bold quantities are vectors) it shows that acceleration and the applied net force are parallel vectors.

- Keeping the mass constant demonstrates a direct proportion between acceleration and the applied net force.

- Keeping the force constant demonstrates an inverse proportion between acceleration and mass.

And of course, you can navigate with the kinematics equations. Just have your mass and net force handy so that you can calculate the acceleration.